Introduction

2016 was another magical year for Chinese science fiction. On the evening of August 20th, Dr. Hao Jinfang was awarded the Hugo Award for Best Novelette for her acclaimed Folding Beijing. This was after Liu Cixin, a Chinese science fiction writer, received a Hugo, undoubtedly the top science fiction award in the world, the second year in a row. It was not only a highlight but a symbol of the rapidly growing Chinese SF.

Three major forces have tremendously shaped the landscape of Chinese SF in recent years: government, capital, and the SF community. In 2016, these three forces joined hands in promoting SF culture in the public and developing SF products in multiple cultural and creative areas such as publishing, movie & TV, drama, comics & animations, games, education, and theme parks.

This article is an attempt to briefly sort out what happened to Chinese SF and to summarize the genre’s noteworthy endeavors and achievements in the past year.

SF as National Agenda

Historically, the trajectory of Chinese SF was at times heavily influenced by top-down political forces. Recently it began to receive continuous and influential support from governments at all levels. On the one hand, following the tradition of focusing on ‘science’ in science fiction, the government re-emphasized SF as a useful instrument for popularizing science and improving the scientific literacy of citizens. On the other hand, due to the high popularity and penetration rate of SF media, it is conceivable that the so-called “SF industry” is often adopted in the governmental agenda for creative and cultural industry development.

In a central government paper regarding promoting citizens’ science literacy issued by State Council in February 2016, it is explicitly stipulated that the government shall support science fiction writing as part of popular science writing. More details were revealed in a later talk given by Han Qide, president of the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST), announcing that CAST will set up a national award for SF and host international SF festivals. The story reached a climax when Vice Chairman Li Yuanchao attended the 2016 National SF Convention held in September 2016 and gave a speech at the opening ceremony warmly encouraging SF writing.

At the local level, the city of Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province, where the Science Fiction World Group (SFWG) resides, proposed building into the “Capital of Science Fiction”. And the city of Sanya, a famous tourism spot in Hainan Province, set up a plan to build a “SF Industrial Base”. As these support policies were put in place recently, their impacts have yet to be seen.

SF as an Industry

“SF Industry” has become a buzz word in the mass media lately. It refers to a portion of creative and cultural industry in which science fiction is supposed to be the central theme. The underlying theory is that science fiction ideas and talents can float between various cultural and creative media such as publishing, films, music, games, education, theme parks etc.

Seeing the skyrocketing demand for local SF products, capital investors are keen to invest in the so-called “SF industry”. Often they choose to partner with insiders from the Chinese SF community. A few notable SF-themed start-up ventures that were quite active in 2016 include Storycom led by Zhang Yiwen, Zhucan Culture founded by SF writer Pan Haitian, Mercury Culture newly founded by SF writer Wang Jinkang, Future Affairs Administration founded by SF activists Ji Shaoting and Li Zhaoxin, and Eight Light-minutes Culture newly founded by SF editor Yang Feng.

Perhaps the most anticipated SF products are Chinese SF movies. Arguably, two big-budget high-box-office Chinese films released in 2016, The Mermaid directed by Stephen Chow and The Great Wall directed by Zhang Yimou, can be regarded as SF movies. However, many people argue that these two blockbusters are more like fantasy movies and they are not entirely “local”. The much anticipated movie adaptation of Three-body Problem (TBP) has postponed its release date to summer 2017. According to multiple sources, dozens of new SF movies are in production too; SF writers or activists are involved in them in different ways. For example, Liu Cixin is listed as a screenwriter of director Ning Hao’s new SF movie Crazy Alien, to be shot this year. We awo years past the so-called “Year Zero of Chinese SF Movies”, yet the Chinese audience is still anxiously awaiting a local “true” or “hard-core” SF movie coming to the cinema.

While the movie is pending, the stage drama adaptation of TBP produced by Lotus Lee Drama Studio hit the market last year and received much acclaim from audiencea and critics. This successful case not only demonstrates the popularity of Liu Cixin and his TBP series once again, but also shows how hungry the Chinese audience is for science fiction media works produced with sincerity.

With strong governmental support and abundant capital inflow, what is going on with Chinese SF? Let us take a look at some sectors in the following part.

Book Publishing

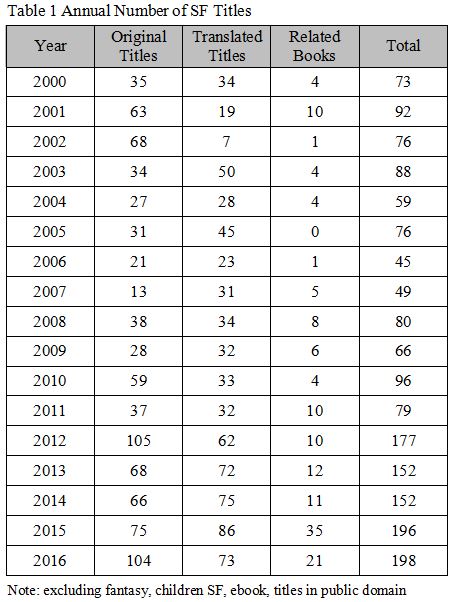

It was the publishing industry that first sensed the upcoming heat of SF, given the wild popularity of TBP, and treated this category as “the next big thing”. The table below summarizes the annual number of SF titles published in China’s book market between 2000 and 2016. It suggests that the total number has suddenly increased from 79 to 177 in 2012 and kept as high as more than 150 in the following years. In 2016, the total number of SF titles hit a record-high 198.

Of all 104 original titles, 49 titles are new novels, 12 are reprint novels, and 43 are anthologies or collections. Notable new SF novels with generally good reviews are Father Heaven and Mother Earth by Wang Jinkang (the sequel to award-winning Escape from Mother Universe), Chasing the Shadows and the Lights by Jiang Bo (the finale of The Heart of Galaxy trilogy), Mechanical Wonder: From the New Daily News by Liang Qingsan (a steampunk story set in 1900s Shanghai), and The Abyss of Time by Fu Qiang (a hard-core detective story set in space).

Short Fiction Markets

The year of 2016 seems like a golden year for SF short fiction. Despite the general decline of the magazine industry, professional print sf magazines are actually thriving. In addition, new professional online markets are emerging and growing, and high-prize writing contests appear one after another. Please refer to an upcoming article of mine for more details.

In 2016, a total of 461 original SF short stories and 117 translated SF&F short stories were published in professional or semi-professional markets. For original SF short stories, it is such a big boost when compared with the number in 2011 (196) or even that in the previous year (362). In particular, the number of published novelettes or novellas jumped from close to zero a couple of years ago to about 40-50, not to mention hundreds of entries submitted to writing contests.

Conventions & Awards

Between September 8th and 11th, a mega-event “2016 Chinese SF Season”, which is comprised of the “2016 National SF Convention” and the “2016 SF Carnival”, was held in Beijing. During the event, a number of high-profile activities were organized (e.g. a National SF Summit, an International SF Round Table, a Chinese SF History Exhibition, and a SF Film Exhibition) and two influential SF awards were presented in succession. The scale and standard of this event are unprecedentedly high. It is indeed a collective effort of the three forces mentioned above.

On its 30th anniversary, the Galaxy Awards were presented on the evening of September 8th. Best Novel was awarded to Dooms Year by He Xi. Three days later, the ceremony of 7th Chinese Nebula Awards was held in the National Library of China. Best Novel was awarded to Jiang Bo for Chasing the Shadows and the Lights, which is the final installment of his epic The Heart of Galaxy trilogy. (see Shaoyan Hu’s report at Amazing Stories)

A couple of new SF awards are noteworthy. First the Droplet Awards, named after a powerful and terrifying alien weapon in TBP, were organized by Tecent to call for submission of SF screenplays, comics and short videos. Best Screenplay was awarded to Day after Day by Feng Zhigang and Best Comic to The Innocent City by Yuzhou Muchang. In addition, the first Nebula Awards for Chinese SF Films were presented at a ceremony held in Chengdu in August 2016. Best SF Movie was given to a 2008 children SF movie CJ7 directed by Stephen Chow. Best SF Short Film was awarded to Waterdrop, a highly praised fan film of TBP, directed and produced by Wang Ren.

Chinese SF in the West

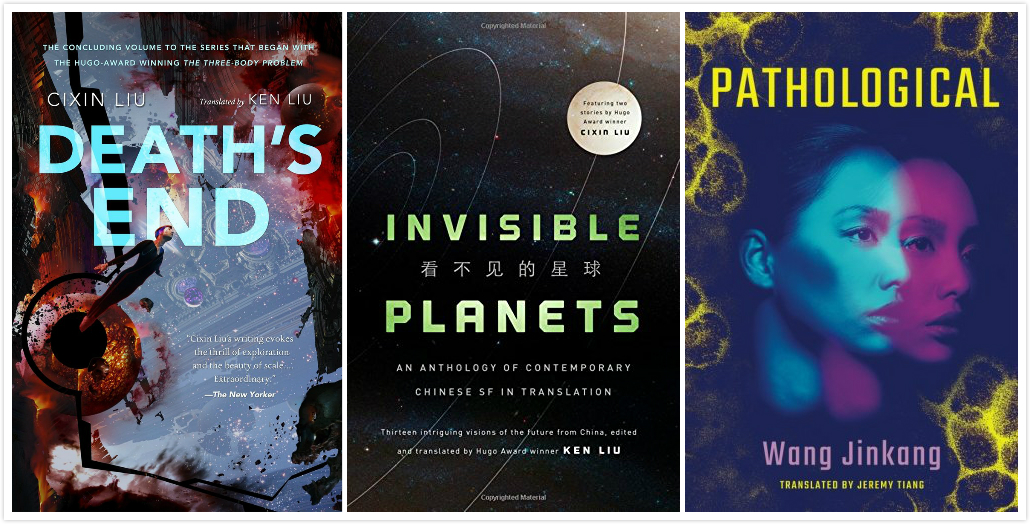

2016 was another productive year for translations of Chinese SF. As usual, our beloved ‘Da Liu’ was the brightest star in this regard. In September 2016, Death’s End written by Liu Cixin and translated by Ken Liu, the much-awaited finale of Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy, was finally released by Tor Books. It hit The New York Times Bestsellers List for Hardcover Fiction (#19) just one week after its release, which is a stellar achievement for a translated fiction. In addition, the Hugo-winning TBP was translated into six different languages (French, Spanish, German, Hungarian, Portuguese and Vietnamese), and was published in multiple countries within just one year. As in the US and UK, TBP was very well received by virtually all the markets. It staid on the German Der Spiegel‘s Bestsellers List for five consecutive weeks (highest rank #4), an unprecedented performance for Chinese fiction. In October 2016, Liu Cixin went on a book tour in Europe and promptly brought a ‘Da Liu Storm’ to the audience on another continent.

Next to Liu Cixin and Hao Jingfang, more and more Chinese SF writers got their feet in the door for publishing stories in foreign markets through different translation projects that collectively showcase the best Chinese SF writing for the world. In November 2016, Tor Books published Invisible Planets: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction in Translation, translated and edited by Ken Liu; the anthology featured 13 stellar stories by 7 of China’s top SF writers and 3 essays examining SF in modern China. The anthology was surprisingly well received by Western readers and got multiple recommendations by SF professionals.

Another remarkable translation project, which was launched in a collaboration between Clarkesworld and Storycom, has stepped into its third year. In 2016, Clarkesworld Magazine published 10 translated Chinese SF stories by 10 young Chinese SF writers. Worth noting is that half of these writers were brand new to the English-speaking market, and a few new translators stood out next to the trailblazing Ken Liu. It is really nice to see that the bridge between Chinese SF and Western SF, as brought up in Liu Cixin’s Hugo acceptance speech, has been growing wider and more robust every year.

In 2016, two SF novels (Death’s End by Liu Cixin & Pathological by Wang Jinkang) and 17 short stories were published in English-speaking markets. Alongside six English language editions of TBP, seven short stories by Chen Qiufan, Zhang Ran and Han Song were translated into French and Italian for publication. No wonder science fiction, perhaps the most globally-oriented and culture-neutral literary genre, is often cited as a rather successful case of central government’s “Chinese Culture Going Abroad” strategy.

Research & Fandom

Little known to the general public, Chinese SF research and fandom enjoyed a colorful and fruitful year in 2016. There is an ever expanding body of Chinese SF research from a community led by Prof. Wu Yan at Beijing Normal University. Dr. Song Mingwei at Wellesley College is another overseas nucleus of the community. Most of the fellows are young post-1980s scholars who grew up reading science fiction, such as Li Guangyi, Ren Dongmei, Wang Yao (a.k.a Xia Jia), Jia Liyuan (a.k.a. Fei Dao), Zhan Ling, Jiang Qian, Jiang Zhenyu, and others.

In 2016, three high quality SF research conferences were held in Haikou, Shanghai and Beijing respectively, covering such topics as Liu Cixin and contemporary Chinese SF, multifaceted Chinese SF literature, and Utopian SF (see Regina Kanyu Wang’s report on Fudan workshop). It is believed by many that such a strong research team will not only provide useful and constructive criticism to the development of the genre, but also bring Chinese voices and models to international SF academia.

As for SF fans, 2016 was simply a fun year. They enjoyed consuming more and more quality Chinese SF works. They went to Beijing to experience the 2016 Chinese SF Season, meeting with Liu Cixin and other SF writers face-to-face. They went to Chengdu to visit SCI-FI Space, a fan-run SF-themed cafe, listening to a theatrical pingshu version of TBP performed by a famous local performer. They even went to Shanghai to join the heated debates and writing workshops organized by local fan community AppleCore.

Closing Remarks

Right after she was given the rocket-like trophy, Hao Jingfang was placed in t he middle of a Chinese media storm. She chose to turn down most interview invitations and returned her focus to research and writing projects. A few months later, she hit the media again with her face on a stylish auto advertisement and her charity project for countryside children sponsored by the auto company. This case exemplified how much gaze, fame, or even resources Chinese SF has gained in 2016 and beyond. It is something that we could never have imagine before.

In the face of such a drastically changing environment, what shall the Chinese SF community do? Liu and Hao among other fellows of the community have already provided a good answer to the question with their actions: make wise use of new resources one has access to; in the meantime, stay humble and stay focused. With this in mind, I believe Chinese SF will be fine no matter what happens in the future.

[originally published at The Shimmer Program, February 12, 2017]

Read my profile

Recent Comments